Running Rust on Lambda

AWS Lambda, at the time of writing, does not support Rust. Fortunately, some wonderful folks have ignored the lack of support and made it work anyways! The main projects I know that allow running rust on Lambda are crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda. There are other notable projects, such as lando and serverless-rust, which use crowbar under the hood.

Given both crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda exist, it seems reasonable to ask “which of these is faster? Which should I use?” This blog post presents a brief introduction to the projects, some toy benchmarks, and some information on usability.

Before getting into that though, let’s talk about how the various methods of running Rust on Lambda work under the hood.

How do they work?

crowbar – Run rust as a python shared library

The crowbar project takes

advantage of the fact that cpython will happily load a shared object file as a

python module.

Writing a cpython module in Rust is fairly easy using the rust-cpython project.

crowbar effectively provides glue code between rust-cpython and Lambda’s python environment.

Various – Spawn a rust binary, talk over stdin/stdout

There are various projects, none of which seem to have gained much traction, which simply provide some abstractions around spawning a child process from the NodeJS environment and passing requests and responses back and forth over stdin/stdout. This works, but each project is defining an ad-hoc protocol for plumbing information between their chosen runtime and Rust, and most of them execute a fresh child process per request, whereas all normal lambda environments re-use one process for many requests.

Because none of them seem very popular and because they vary wildly in quality, I’ve skipped over them entirely in my comparison.

Rust on AWS Lambda – Just sorta look like Go, you know?

After the creation of the previous two methods of running Rust on Lambda, Lambda released support for Go. The way Lambda’s Go support works is by launching a binary the user uploads and then speaking a specific RPC protocol to it over a TCP port. AWS provides a library to make it easy to do this in Go, but there’s no reason the zip file actually has to contain a Go binary.

Rust on AWS Lambda runs Rust code in the Go Lambda environment, and unlike the previous two methods, it doesn’t require any non-Rust code at all. Rust on AWS Lambda implements the same protocol AWS’s Lambda Go library does, and provides additional library code to ease writing a handler function.

Benchmarks – Which way is the fastest?

One thing to consider when picking a method of running Rust code on Lambda is how fast it is. In this section, I present the results of benchmarking each of these methods along with a non-Rust function using the same language environment. Unfortunately, these results may change over time with no notice due to AWS updating or changing how they run Lambda functions.

I’m just trying to measure the overhead of the framework and runtime environment, not the actual code being run, so I’m measuring a trivial “hello world” example (given an empty payload) in each case.

I’m specifically benchmarking the following environments.

- Go (using Go code)

- Go (using Rust on AWS Lambda)

- Python (using python code)

- Python (using crowbar to run Rust)

Prior Art

This medium post by Nathan Malishev benchmarks the cold start time for various runtimes. However, none of the benchmarks included Rust anywhere in the mix, and the numbers appear to have changed since then. Nonetheless, I feel it’s necessary to mention this blog post as it served as an inspiration for my methodology (using XRay to measure execution time) and gave me a baseline to compare against.

Since that blog post did not share detailed information on its methodology (to the point of not even mentioning the region being benchmarked), I had to effectively start from scratch.

Methodology

All of the lambda functions, benchmark code, and results are available in this repository.

All of data was collected within 3 days of September 14th, 2018 in the

us-west-2 region. This matters because Lambda’s performance will doubtlessly

change over time (hopefully for the better).

I measured “cold” and “warm” starts. For my purposes, a lambda’s start was

considered to be “cold” when no other Lambda functions had been executed in that AWS

account for 45 minutes.

A “warm” start was considered to be any additional run within a short period,

under a minute, after a previous execution of the function in question.

In practice, this meant my data was collected by going through the following steps:

- Create 4 lambda functions, each printing “Hello World” from a different framework.

- Wait 45 minutes

- Execute one function (cold)

- Wait 10s

- Execute the same function (warm)

- Go to step 2 until all functions have been executed

- Collect XRay traces for all previous function executions and store them

Note that it turns out that the above is overly cautious. Simply creating and immediately executing a lambda function seems to give fairly similar times as waiting 45 minutes and executing it, so I could have saved numerous hours by simply creating a lambda, collecting a cold and warm data points, deleting it, and continuing to the next one in a similar fashion.

Despite the slow methodology I chose, I still managed to parallelize it by using several AWS Organization accounts dedicated to this purpose. Since each account is largely independent, I could parallelize data collection between them without a worry of accidentally heating up other Lambdas.

One final precaution I took (which is also unnecessary I believe) was to toss a few random bits into each uploaded zip file to ensure none of them could be cached.

Results

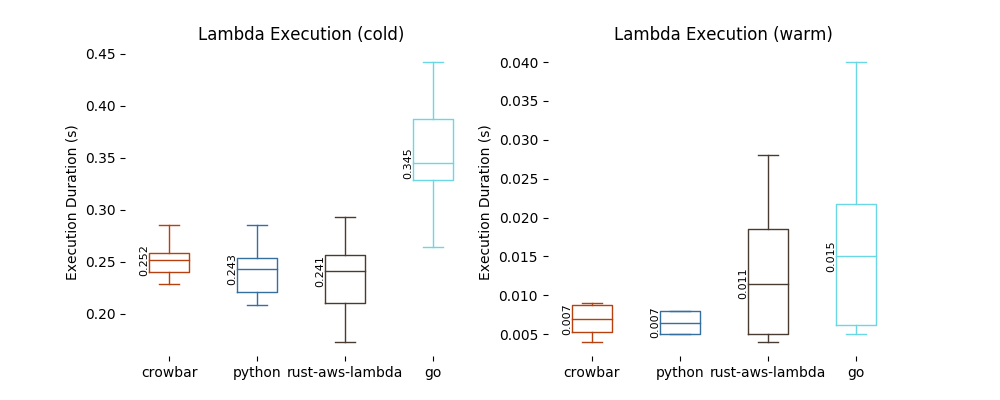

And now for the results! The below graph shows data collected over around 40 executions of each Lambda function (half warm and half cold). The median value is annotated beside each box.

The raw data is available here if you wish to process it for your own purposes.

The main data I was interested in was the cold execution time. We can immediately see, at a glance, that python, crowbar, and Rust on AWS Lambda all have very similar cold execution times (at around 250ms), while Go’s cold-start time is drastically slower, and more variable as well. In fact, this chart omits outliers, or else there would be one 739ms data point for Go… None of the other functions had such an extreme outlier.

Rust on AWS Lambda generally was slightly quicker than the other frameworks by a small margin and it also had the fastest cold start time measured, at 173ms. This still pales in comparison to every warm start (the slowest of which was 104ms, a significant outlier from Rust on AWS Lambda’s warm executions).

Speaking of warm starts, crowbar and python were neck-and-neck, and both handily beat Go and Rust on AWS Lambda by good margins. Of course, these margins are measured in milliseconds, so it will almost certainly vanish in the noise of a Lambda doing real work, not just printing “Hello World”.

I suspect that part of the cold start time can be attributed to the size of each deployment zip.

| Function | Zip file size | Uncompressed size |

|---|---|---|

| python | 245 B | 85 bytes |

| crowbar | 774 KB | 2.91 MB |

| go | 4.2 MB | 8.41 MB |

| Rust on AWS Lambda | 1.6 MB | 5.17 MB |

As I understand it, on each cold start Lambda will download the deployment zip file from S3 and extract it. That means the startup time will include the time it takes to copy the bytes over the network and the time it takes to write them to disk. Since this is within the same region (and probably same AZ), these times should be quite small, but the differences I’m measuring on cold starts are already fairly small. The difference in size between Go binaries and the other binaries is the best explanation I’ve got for why Go’s so slow here.

So is crowbar faster?

The sample size is not large enough to conclusively call one or the other faster for cold starts. I think it is fair to say that crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda both perform quite well.

There are also additional factors which this benchmark ignored, but may matter in real-world environments. For example, normally the size of the deployment zip file between crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda would differ by a smaller percent since the function handler would be larger, but the framework only introduces a constant increase in size. If the size of the deployment zip file is significant, a real world deployment would likely show better numbers for Rust on AWS Lambda.

Most real world deployments will also pass complicated JSON data to the function, not just an empty string. The details of how the Python and Go environment pass in parameters could have different performance characteristics.

Given the benchmark run here, it’s reasonable to conclude both crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda perform similarly, but additional experimentation and data could result in a different, more refined, conclusion.

Ease of Use

Now that we’ve seen both crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda have similar performance, let’s look at the ease of use of each.

crowbar

It took me longer to get a working crowbar Lambda function than all the other test function’s combined. Building a dynamically linked shared library in Rust is fairly easy. Building one for a cloud environment that might have a broken python configuration is a bit harder.

The rust-cpython crate is great,

but it’s also difficult to debug. If you’re curious, it invokes python code

like so

to determine various linker flags rather than invoking the more standard

pkg-config.

Ultimately, I had to add this strange line to my Makefile to get my crowbar Lambda function to link at all.

Furthermore, I hear I’m getting off easy because I don’t have to deal with

linking against openssl,

just libpython3.6m.

Rust on AWS Lambda

That’s not to say Rust on AWS Lambda is a blameless holy project either. I

wanted to just type cargo build --release, zip it up, and be done, but the reality is less ideal.

Sure, I didn’t have to deal with a strangely packaged python library, but

Lambda’s copy of glibc is old enough no modern Linux distribution will build

a working binary by default.

Fortunately, the lambci project has a wonderful go-build image which makes building a Rust on AWS Lambda function fairly straightforward.

It’s also possible to create statically linked Rust binaries using musl, but

I’ve found that to be tricky in the past so I went with the docker approach.

Conclusion

I found Rust on AWS Lambda to be easier to get deployed. Both crowbar and Rust on AWS Lambda required building in a docker container due to library differences, but for Rust on AWS Lambda, that was the only hurdle to leap over.

On the performance front, I think both Rust on AWS Lambda and crowbar perform quite well, and I suspect they’ll have very similar performance for real workloads, though further experimentation on that front may be needed.

I think that they’re both great projects, but I personally will be using Rust on AWS Lambda to fulfill my next Rust-based Lambda function need.

In conclusion, here’s one last table to explain why I think you might prefer one or the other:

| Feature | Crowbar | Rust on AWS Lambda |

|---|---|---|

| Pun in name | ✓ | ✗ |

| Faster than Go | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pure Rust | ✗ | ✓ |

| Cold startup overhead | ≈ 250ms | ≈ 240ms |

| Warm startup overhead | ≈ 7ms | ≈ 10ms |

| Requires linking to python | ✓ | ✗ |